CLICK ON THE MAIN PHOTO ABOVE TO VIEW CAPTIONS IN GALLERY FORMAT

Image 1: Reviewed in collaboration with DWB. See here for full version.

Buddhist cuisine, better known in Japan as shōjin ryōri (精進料理), is a cuisine of devotion that follows the Buddhist philosophy of persistency to incorporate austere practices. If it wasn’t for the insistence of @FramedEating to try this Two-Michelin starred restaurant we would have missed out on one of the highlights from our entire trip across Japan.

Image 2: Nomura Yoshiko, who founded Daigo restaurant near Daigo-ji temple in 1950, remained as the okami (female lady of the house / supervisor) of the establishment until the restaurant relocated to a more modern location next to Seisho-ji temple at the foot of Mt. Atago in Tokyo.

Image 3: The current premises of the restaurant works perfectly well and you still get that genuine feeling of entering an old temple despite the modern surrounding. Daigo continues to be a family affair where Nomura Satoko oversee’s the guests arrival as the current okami, supported by her husband Nomura Masao (president) and three sons who run the restaurant that are Nomura Yusuke (restaurant manager) and Nomura Daisuke (head chef).

Image 4: Word of warning though for those who are not used to Japanese customs. You will be required to take off your shoes at the entrance before you are shown to one of the eight private rooms available on the premises. All the rooms have tatami floors with a view over their own private Japanese garden. Impressively there was an almost complete absence of any noise from the neighbouring rooms given there were only a couple of shōji’s (rice paper wall) separating us.

Image 5: Our reservation fell on a rather hot and humid evening and the ice chilled apperitif or shokuzenshu (食前酒) of the Umeshu plum wine (梅酒) with a scented wet napkin to freshen up was a very welcomed gesture to our arrival.

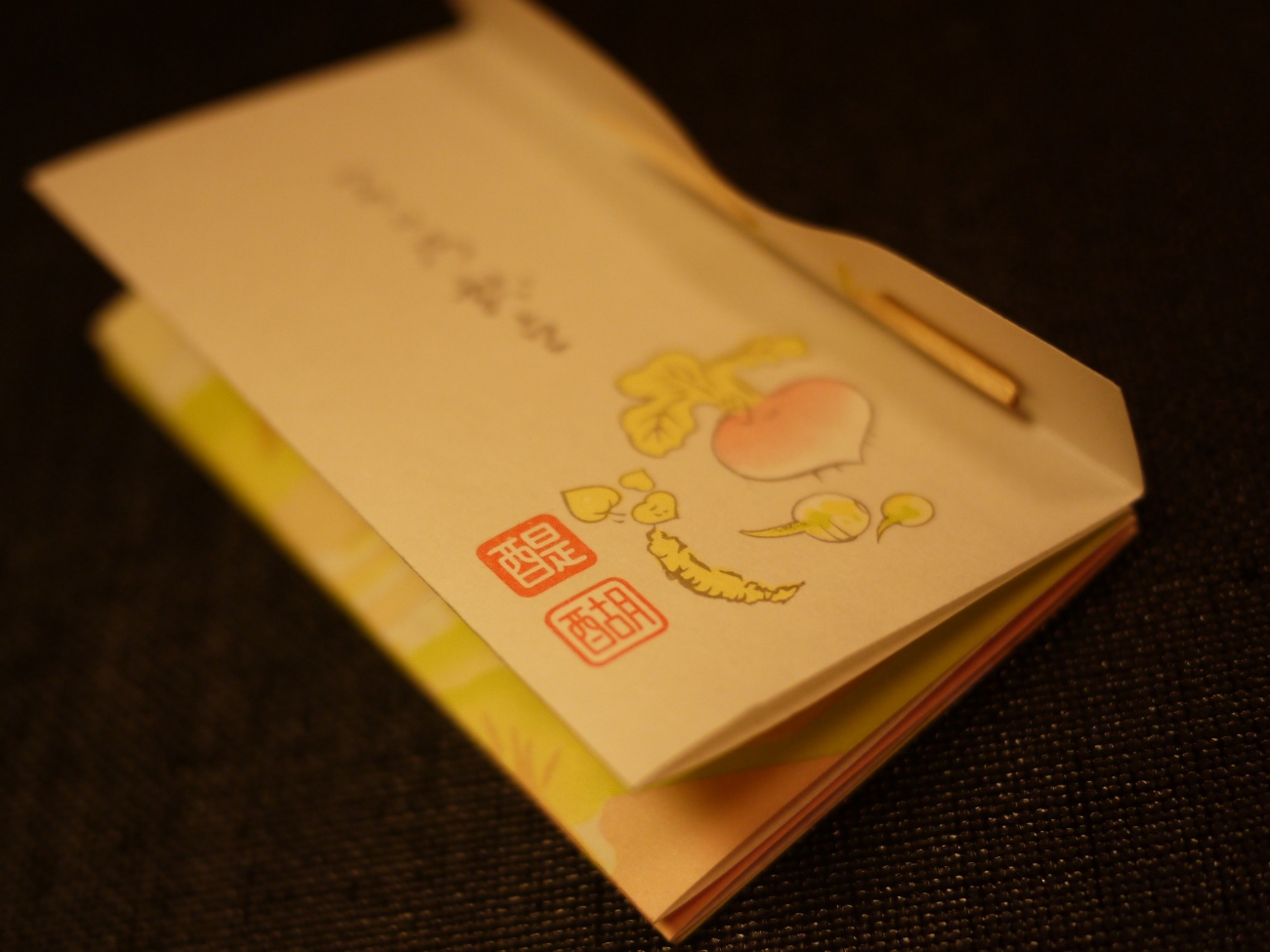

Image 6: As the sake was being poured, another waitress proceeded to serving us our Zensai (前菜), otherwise known as the Starter, on a beautiful lacquered tray with a pair of chopsticks that we were encouraged to take home after our meal.

Image 7: Our first course was the chef’s interpretation of Tsukimi Dango (月見団子), a typical dumpling served for the moon-viewing festival (Tsukimi) that dates back to the Heian period, roughly a thousand years ago. Four lightly fried dumplings of Edamame, Corn, Rice and Sesame were served that were all distinctly flavoursome as well as crispy, warm and void of any excess oil. Not a bad start at all.

Image 8: The dumplings came with a Kotsuke (小附), a small supplement dish called Shikisaikurouyose (色彩九郎寄せ) and Suizenjinori (水前寺海苔) served in a long ceramic case. It was essentially a herbaceious gel of dashi stock containing shiso (perilla) leaves and seaweed from Suizen-ji temple. The strong sweet and spicy flavour really drew the clean flavour of the dashi.

Image 9: Next was the clear soup course or Osuimono (御吸物), an aromatic Kaburamushi (蕪蒸し), essentially a turnip that had been steamed, peeled and grated before reassembling it into a small ball and serving it in a clear soup with the young leaves of Japanese pepper, kinome (木の芽), and yuba (tofu skin). It had a soft texture and distinct but subtle flavour of turnip; far superior to any kaburamushi I’ve previously.

Image 10: The filler course to tie to the next dish, also known as an Oshinogi (お凌ぎ), was an assortment of Vegetable Sushi (野菜寿司) made from Green pepper (ピーマン) with black sesame and salt crystals, Bamboo shoot – Takenoko (筍), Shiitake mushroom (椎茸), Fermented seaweed and Cucumber – Kappamaki (河童巻). Each sushi was remarkably delicious and varied in sweetness, and seasoning to complement each ingredient.

Image 11: The next dish, the Hassun (八寸) is perhaps the most poetic and constrained course in a kaiseki meal. The tray typically contains two types of food representing “mountain” and “sea” that depict and celebrate the current season. The food is arranged across the tray in tiny piles to create contrasts of color, shape, texture, and seasoning. It is been generally recognised in Japan that a person with sensitivity to the changing season is one that possesses talent.

Image 12: The Nimono (煮物) or simmered dish course was a Tougan agedashi (冬瓜揚げ出し) presented in a ceramic bowl covered with a lid. The fragrant aroma that wafted out was sensational and put us under a spell. The slight heat from the ginger, fragrance of the spring onion and the sticky texture of the rice ball – all came together with the thick dashi sauce. What a phenomenal dish!

Image 13: Our Agemono (揚物), or deep fried course, was Daigo’s Shyoujin-age (精進揚げ) consisting of a variety of tempura from maitake (hen-of-the-woods mushroom), shikakui-mame (winged bean), sweet pumpkin, tofu and shallots. The tempura here was far more interesting and well balanced in texture and flavours than Raku-tei. I particularly liked the rice pop corn that was salty and packed with so much flavour.

Image 14: There was a significant pause before Nomura-san came back with our next course. However, contrary to what we expected based on the copy of the menu we were given, a special course of Japanese fig or Ichijiku (無花果) was brought to us on the house.

Image 15: The fig had been prepared in a sakamushi style, that is steamed with sake, and served with a white miso glaze on top. It was by far the best fig dish I have ever tried with a beaitful marriage of sweet and savoury flavours and a melting texture to die for. We were left speechless as Nomura-san came back to collect our empty dishes. We must have looked like a bunch of guppies.

Image 16: The Shiizakana (強肴) is traditionally served to customers after the fried dish as a relish to further enjoy with the sake of choice. On this occasion we were served a Matsutake Mizoreae (松茸霙和え), that is pine mushroom prepared with grated daikon radish, and Kaki Shishitou (柿獅子唐) which were slithers of persimon and slightly hot shishitou peppers. I’m not the biggest fan of matsutake mushrooms but this wasn’t too bad as far as it went.

Image 17: Our palate cleanser, or Hashiarai (箸洗) was served in a beautiful ceramic cup that contained Chikushi Konbu (竹紙昆布) which was a soup made of a luxurious konbu, garnished with slithers of the konbu itself and puffed rice balls. It was very soothing and aromatic again. Despite having quite a few dishes we felt energised at this point as the food had been light, aromatic and harmonious in progression.

Image 18: The Gohan (御飯) or rice dish came on a lacquered tray and was our ultimate savoury dish of the evening. It contained…

Image 19: ... a bowl of Nameko Zousui (なめこ雑炊), basically a rice porridge dish prepared in a stock made from nameko mushroom served with gooey nameko and enoki mushrooms. The food here was not only delicious but also thoughtful. The concentrated flavour of mushrooms was stunning and the lingering flavour in our mouths delightful. This was indeed what Japanese people call soul food.

Image 20: Our meal finished with a couple of sweet dishes starting with the Mizunomono (水の物) which on this occasion was an unbelievably juicy and sweet slice of melon and grapes and…

Image 21: … we had a cup of the best cold red bean soup with mochi – Shiratama zenzai (白玉善哉) – I have ever had the pleasure of eating. The flavour of the red bean had been further drawn out with kurozatou or black sugar but without making it sickeningly sweet.

We came with little expectation and left speechless. Shoujin ryouri has countless limitations in its cooking methods and is intertwined with Japanese traditions, culture and arts.

Image 22: In a culinary age that could be perhaps described as gluttony from the abudance of food, a cuisine following the austere discipline of Buddhism is a fresh breath of air. The only thing I didn’t agree was the star rating bestowed by Michelin. This was far superior to many Three-starred establishments we had collectively visited. If Daigo isn’t on your list then I would strongly urge you to add it.